Humans have wondered about the stars since forever. That’s understandable; they’re beautiful and mysterious, as out of reach as mountain peaks. And perhaps for the same reasons, the earliest speculation about the stars revolved around gods, not extraterrestrials.

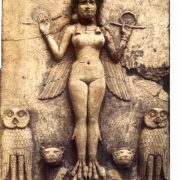

As with mountains, humans have associated stars with deities since the beginning of human history. Three of the most important gods in the ancient Near East, from Sumer to Israel and its neighbors, were the sun, moon, and the planet Venus. To the Sumerians they were the deities Utu, Nanna, and the goddess Inanna; later, in Babylon, they were Shamash, Sîn, and Ishtar. The Amorites worshiped Sapash, Yarikh, and Astarte—who was also the god Attar when Venus was the morning star (and here you thought gender fluidity was a new thing).

God not only recognized that the nations worshiped these small-G gods, He allotted the nations to them as their inheritance—punishment for the Tower of Babel incident.

When the Most High agave to the nations their inheritance, when he divided mankind, he fixed the borders of the peoples according to the number of the sons of God. (Deuteronomy 32:8)

And beware lest you raise your eyes to heaven, and when you see the sun and the moon and the stars, all the host of heaven, you be drawn away and bow down to them and serve them, things that the LORD your God has allotted to all the peoples under the whole heaven. (Deuteronomy 4:19)

In other words, God placed the nations of the world under small-G “gods” represented by the sun, moon, and stars, but He reserved Israel for Himself. The descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were to remain faithful to YHWH alone, and through Israel He would bring forth a Savior.

But the gods YHWH allotted to the nations went rogue. That earned them a death sentence.

God has taken his place in the divine council;

in the midst of the gods he holds judgment:

“How long will you judge unjustly

and show partiality to the wicked? Selah […]

I said, “You are gods,

sons of the Most High, all of you;

nevertheless, like men you shall die,

and fall like any prince.” (Psalm 82:1, 6–7)

To be clear: Those small-G gods are not to be confused with the capital-G God, YHWH, the Creator of all things including those “sons of the Most High.” Theologians and Bible teachers generally treat the gods of Psalm 82 as humans, usually described as corrupt Israelite kings or judges. With all due respect, they’re wrong. The most obvious error in their view is that verse 7—“nevertheless, like men you shall die”—makes no sense if God is addressing a human audience.

No. When the Bible says “gods,” it means gods.

There are other, more technical reasons to view the divine council as a heavenly royal court. We direct you to Dr. Michael S. Heiser’s excellent website, www.TheDivineCouncil.com, for accessible, scholarly, biblical support for this view.

Seriously, go there and read. Understanding the divine council view is critical to really grasping much of what’s going on throughout the Old Testament: Supernatural beings have exercised the free will they were created with to rebel against their Creator. As Christians, this should be our default view. After all, Paul spelled it out:

For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places. (Ephesians 6:12)

Rulers, authorities, cosmic powers, spiritual forces of evil. Those aren’t concepts, ideas, or random acts of misfortune. Paul was warning us about supernatural evil intelligences who want to destroy us. And guess what? At least some of them are “in the heavenly places.”

We’ll refer to that verse many times in this book. Ephesians 6:12 is key. As our friend Pastor Carl Gallups likes to say, spiritual warfare is a lot more than finding the willpower to pass up a second bowl of ice cream.

Why this detour though the Bible? Two reasons. First, to document that humanity has looked to the stars as gods for at least the last 5,000 years, as far as Babel and probably beyond. And second, to set the stage for what we believe official disclosure is truly about—the return of the old gods.

You see, the Enemy has been playing a very long game. Once upon a time, Western civilization generally held a biblical worldview. The influence of the spirit realm on our lives wasn’t perfectly understood, but at least it was acknowledged. And while the church of Rome can be fairly criticized for keeping the Bible out of the hands of lay people for nearly a thousand years, the scholars and theologians of the church made a fair effort to interpret their world through a biblical filter.

How have we become so secular in our worldview? It appears that the principalities and powers have nudged and prodded humanity through the Enlightenment, then Modernism and Postmodernism to move modern man from a supernatural worldview to one that could believe in an external creator while denying the existence of a supernatural Creator.

Hence, ancient aliens.

In other words, to accept our ET creator/ancestors we first had to reject the biblical God. In 1973, British science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” By substituting advanced science for the supernatural, ancient alien evangelists are spreading a sci-fi religion for the 21st century. It offers mystery, transcendence, and answers to those nagging Big Questions. And best of all, ETI believers don’t need to change the way they think or act.

This view found fertile intellectual soil in areas influenced by Greek philosophy. The evidence is compelling that the rise and spread of Greek thought has run parallel with the belief in life among the stars.

A pause here for a big “thank you” to author and artist Jeffrey W. Mardis. His excellent book What Dwells Beyond: The Bible Believer’s Handbook to Understanding Life in the Universe was very helpful in guiding Josh Peck and me as we researched our book, The Day the Earth Stands Still. Rather than rewrite his work, however, we’ll summarize here the emergence of cosmic pluralism, the concept that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, and then suggest you get a copy of What Dwells Beyond for your personal reference library.

The idea that there are more inhabited worlds in the universe than just our own isn’t new. It dates to six centuries before the birth of Jesus, about the time Nebuchadnezzar led the army of Babylon across the ancient Near East to conquer, among other nations, the kingdom of Judah. A Greek philosopher, mathematician, and engineer named Thales of Miletus (c. 620 B.C.—c. 546 B.C.) is credited with being the father of the scientific method. According to later philosophers, Thales was the first to reject religious cosmology in favor of a naturalistic approach to understanding the world. Among his theories was the belief that the stars in the night sky were other planets, some of which were inhabited.

The influence of Thales is felt even today. While there are benefits to searching for the natural causes of, say, earthquakes rather than attributing them to the temper of Zeus, denying the influence of the supernatural altogether has blinded science in many fields of inquiry. For example, researchers into the effects of prayer tend to focus on the physiological benefits. It reduces stress and makes you “nicer.”

Well and good, but since prayer is a hotline to the Creator of all things, could there be more behind the benefits of prayer than just sitting quietly? Is it possible that people who pray are nicer and more relaxed because they’ve tapped into what the apostle Paul called “the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding”?

To a scientist with a naturalist bias, the answer is, “Of course not.” Since God can’t be observed and quantified, He must not exist. And so extra “niceness” is a result of what can be observed—the physical act of talking to (in their minds, an imaginary) God.

The intellectual descendants of Thales included influential thinkers such as Pythagoras, who in turn influenced Plato, as well as Democritus and Leucippus, who developed the theory that everything is composed of atoms. Epicurus, building on the teaching of Democritus, proposed that atoms moved under their own power, and that they, through random chance, clumped together to form, well, everything—matter, consciousness, and even the gods themselves, whom Epicurus believed were neutral parties who didn’t interfere in the lives of humans.

It’s clear that Epicurus and his followers have had quite an influence on modern thought. Interestingly, about three hundred years after the death of Epicurus, Paul encountered some Epicureans (and their philosophical rivals, the Stoics) on Mars Hill in Athens. Epicurus, cited by the early Christian author Lactantius, is credited with posing what’s called The Problem of Evil:

“God,” he says, “either wants to eliminate bad things and cannot, or can but does not want to, or neither wishes to nor can, or both wants to and can. If he wants to and cannot, then he is weak – and this does not apply to God. If he can but does not want to, then he is spiteful – which is equally foreign to God’s nature. If he neither wants to nor can, he is both weak and spiteful, and so not a god. If he wants to and can, which is the only thing fitting for a god, where then do bad things come from? Or why does he not eliminate them?”

I know that most of the philosophers who defend [divine] providence are commonly shaken by this argument and against their wills are almost driven to admit that God does not care, which is exactly what Epicurus is looking for.

You can see why the Epicureans wanted to tangle with a preacher of the gospel of Jesus Christ—they must have thought Paul would be an easy target. Ha!

Of course, this so-called problem is often presented as “proof” that God doesn’t exist. Epicurus’ thought exercise assumes that there is only one god (and there is, in fact, only one capital-G God, YHWH, but the Bible clearly names multiple small-g gods, and God Himself calls them gods) who is responsible for everything, good and bad, that happens on Earth. In other words, to satisfy the Epicureans, free will would be eliminated for every being in creation except the Creator, because to eliminate bad things requires eliminating the power of people who want to do them.

And yet the philosophy of Epicurus—that everything is the product of natural processes, even the supernatural—dominates Western thought, even though most people who hold it have never heard of Epicurus.

It’s no coincidence that the influence of the Greek philosophers faded with the spread of Christianity. The materialistic bias of Greek thought was pushed back for a time by the supernatural power and message of the gospel. To be blunt, when you follow materialist philosophy to its logical end, you’re left with the worldview of Epicurus—the only goal in life is to pursue pleasure and avoid pain.

Why? What’s the point of that? How would Epicurus answer the Big Questions: Where do we come from, why are we here, and where do we go when we die? The Epicurean view of life is depressingly bleak: We come from nothing through random natural processes; our purpose in life is to avoid being hurt; and we go nowhere when we die because our souls cease to exist.

Nothing, nothing, and nothing. That’s what a materialist worldview offers.

And yet it came storming back after more than a thousand years underground with the dawn of the so-called Age of Reason, the Enlightenment. Ironically, the emergence of Islam in the seventh century may be partly responsible for holding back the influence of Greek philosophy in the West. After the first great wave of Muslim expansion wiped out Christianity in northern Africa, travel from the Eastern Roman Empire to Western Europe became more difficult as travel across the Mediterranean was no longer safe. It was only after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and the wave of refugees who fled west to Christian Europe with copies of the works of ancient Greek thinkers that the Enlightenment took root.

And those ideas are blooming now in the twenty-first century.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!