One of the giants killed by David and his men during Israel’s war with the Philistines carried the unusual name Ishbi-benob. It’s usually taken to mean “his dwelling is in Nob.” However, as we mentioned last month, that’s an error. Given that the Hebrew word ôb means “medium” (or, more accurately, “necromantic ritual pit”), the giant wasn’t Ishbi-benob, he was Ishbi ben Ob. or “Ishbi son of the medium.”

But this goes even deeper. ʾÔb, in turn, is related to the Hebrew word ʾab, which means “father.” In the Old Testament, the word “fathers” most often refers to one’s dead ancestors. For example:

And when the time drew near that Israel [Jacob] must die, he called his son Joseph and said to him, “If now I have found favor in your sight, put your hand under my thigh and promise to deal kindly and truly with me. Do not bury me in Egypt, but let me lie with my fathers [ăbōṯ]. (Genesis 47:29–30)

Looking at all of this in context, then, we can pretty safely say that Oboth, one of the stations of the Exodus named in Numbers 21:10–11 and Numbers 33:43–44, essentially means “Spirits of the Dead.”

The other location mentioned in those verses, Iye-abarim (or “ruins of the Abarim”), is based on the same root. Abarim is the anglicized form of ōbĕrîm, a plural form of the verb ʿbr, which means “to pass from one side to the other.” In this context, it refers to a spirit that passes from one plane of existence to another, or crosses over, in the same sense that the ancient Greeks believed that the dead traveled across the River Styx to reach or return from the underworld.

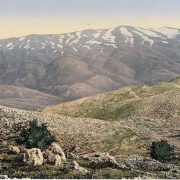

The placement of Oboth and Iye-abarim in Numbers 33 suggests that they were east of the Dead Sea, close to Mount Nebo and the plains of Moab. This is confirmed by the proximity of Shittim to Beth-Peor. And that’s a name that needs a deeper dive.

Peor is related to the Hebrew root p’r, which means “cleft” or “gap,” or “open wide.” In this context, that’s consistent with Isaiah’s description of the entrance to the netherworld:

Therefore Sheol has enlarged its appetite and opened [pa’ar] its mouth beyond measure. (Isaiah 5:14)

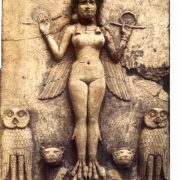

This is similar to the Canaanite conception of their god of death, Mot, who was described in Ugaritic texts as a ravenous entity with a truly monstrous mouth:

He extends a lip to the earth, a lip to the heavens, he extends a tongue to the stars.

It appears, then, that Baal-Peor was the “lord of the entrance to the netherworld.” So, Beth-Peor, the “house (or temple) of the entrance to the netherworld,” was near the plains of Moab and Mount Nebo—which God called “this mountain of the Abarim.”

All of this leads to the real reason God was angry with the Israelites when they camped at Shittim. The worship of Baal-Peor was not about sexual fertility rites, as you might think after reading the story of the zeal of Phinehas.

Then they yoked themselves to the Baal of Peor,

and ate sacrifices offered to the dead;

they provoked the Lord to anger with their deeds,

and a plague broke out among them.

Then Phinehas stood up and intervened,

and the plague was stayed. (Psalm 106:28–30, emphasis added)

Writing four hundred years after the incident at Shittim, the psalmist didn’t even mention the young couple caught in the act by Phinehas. It was eating sacrifices offered to the dead that angered Yahweh. And judging by the words of later prophets, the Israelites were slow to learn their lesson.

But you, draw near,

sons of the sorceress,

offspring of the adulterer and the loose woman.

Whom are you mocking?

Against whom do you open your mouth wide

and stick out your tongue?

Are you not children of transgression,

the offspring of deceit,

you who burn with lust among the oaks,

under every green tree,

who slaughter your children in the valleys,

under the clefts of the rocks?

Among the smooth stones of the valley is your portion;

they, they, are your lot;

to them you have poured out a drink offering,

you have brought a grain offering.

Shall I relent for these things? (Isaiah 57:3–6)

Isaiah wrote nearly seven hundred years after the Exodus, but the Israelites were still engaged in the occult practices that compelled God to smite them with a devastating plague. To “burn with lust among the oaks” suggests fertility rites, which seems obvious given the prophet’s condemnation of the children of the adulteress and “loose woman,” which is also rendered “prostitute” and “whore” in other English translations. Ah, but once again, there is more in the Bible verse than meets the English-reading eye.

The Hebrew word translated “sorceress,” ʿanan, is difficult to pin down. “Witch” and “fortune teller” have also been used in translation. More likely, however, is a correlation with the Arabic ʿanna, meaning “to appear,” which suggests that the sorceress was actually a female necromancer.

This may explain why the word rendered “oaks” or “terebinths,” normally spelled ʾêlîm, is ʾēlîm in Isaiah 57:5. This could be a scribal error, but it seems more likely that it’s the same word we find in Psalm 29:1:

Ascribe to the Lord, O heavenly beings (bənē ʾēlīm),

Ascribe to the Lord glory and strength.

As we saw above in the story of Saul and the medium of En-dor, elohim and its shortened form, elim, was used in Hebrew to refer to dead ancestors. So, Isaiah wasn’t necessarily railing against sex rites among the sacred oaks, but rather something like, “You sons of the necromancer…who burn with lust among the spirits of the dead.” It’s likely the prophet was engaging in the wordplay for which he’s well known, using a pun to emphasize the spirits behind the rituals—the ʾêlîm among the ʾêlîm.

Isaiah continues his diatribe by connecting the death cult to the rites of Molech. The valley of the son of Hinnom, later called Gehenna, was the location of the tophet, where Israelites sacrificed their children to the dark god of the underworld. The Valley of Hinnom surrounds Jerusalem’s Old City on the south and west, connecting on the west with the Valley of Rephaim (interesting coincidence) and merging with the Kidron Valley near the southeastern corner of the city. It’s as Isaiah described it, a narrow, rocky ravine that was used as a place for burying the dead. Tombs along the sides of the valley are plainly visible to visitors to Jerusalem today. This helps us better understand the real meaning behind verse 6, which begins, “among the smooth stones of the valley is your portion.”

An alternative understanding of the phrase challeqe-nachal, “smooth things of the wadi,” is the “dead” of the wadi. This meaning is based on examples of the related Semitic word chalaq found in Arabic and Ugaritic with the meaning “die, perish.”

The brings the picture into focus. This chapter of Isaiah is obscure and hard to understand only if we read it without understanding what the prophet knew about the Amorite cult of the dead. This is confirmed by the next few verses of the chapter:

On a high and lofty mountain

you have set your bed,

and there you went up to offer sacrifice.

Behind the door and the doorpost

you have set up your memorial;

for, deserting me, you have uncovered your bed,

you have gone up to it,

you have made it wide;

and you have made a covenant for yourself with them,

you have loved their bed,

you have looked on nakedness.

You journeyed to the king with oil

and multiplied your perfumes;

you sent your envoys far off,

and sent down even to Sheol. (Isaiah 57:3–9)

The high places were almost constantly in use in Israel and Judah, even during the reigns of kings who tried to do right by God, like Hezekiah. The imagery of adultery and sexual license is a common metaphor in the Old Testament for the spiritual infidelity of God’s people. But even here, there are some deeper things to bring out.

This section of Scripture confirms that the target of Isaiah’s condemnation was a cult of the dead. Because Hebrew is a consonantal language (no vowels), similar words in the original Hebrew text, written before diacritical marks were used to indicate vowels, can be confusing. Verse 9 is a case in point. The consonants mem, lamed, and kaph can be used for melech (“king,” which is how it’s interpreted in Isaiah 57:9), malik (“messenger,” especially as a type of angel), or the name of the god Molech. Considering what precedes that verse, specifically Isaiah’s reference to slaughtering children in the valleys, the latter option is most likely.

So, Isaiah 57:3–9 should be understood as God’s condemnation of the worship of the dead. Isaiah calls out the “sons of the necromancer” who “burn with passion” among the spirits of the dead, sacrificing their children among the dead of the wadis, who were offered food and drink consistent with the Amorite kispum ritual for the ancestral dead. But it was worse than that—the apostate Jews “journeyed to Molech with oil…and sent down even to Sheol,” the realm of spirits worshiped as the long-dead, mighty kings of old.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!