If the Bible’s condemnation of an ancient race of giants and the supernatural entities who created them—in other words, the Nephilim and the “sons of God” from Genesis 6—was unique among the religious texts of the ancient world, you’d be right to be skeptical. But that happens not to be the case. Similar stories, told from slightly different perspectives, are attested in many of the cultures in the ancient Near East. Mesopotamians knew the Watchers as supernatural sages called apkallu. They were agents of the god Enki, lord of the abzu (“abyss”), who sent them into the world to deliver the gifts of civilization to humanity.

Despite this, the apkallu were considered potentially dangerous, capable of malicious witchcraft. An Assyrian exorcism text names two apkallus who angered gods and thus brought punishment on themselves and the land, and in a popular Mesopotamian text called the Epic of Erra, the chief deity Marduk tells of how he banished the apkallus to the abzu (after he caused the Flood!) and told them not to return to the earth. That’s exactly the punishment God decreed for the Watchers, likewise connected to the great deluge remembered for centuries across Mesopotamia.

Interestingly, the last four apkallus were described as partly human, and thus able to mate with human women, just like the Watchers and their offspring, the Nephilim.

The giants created by the lecherous Watchers were destroyed in the Flood of Noah. While the Bible doesn’t make this explicit, it’s implied in 1 Peter 3:18–20, where the apostle links the Flood to the angels who “formerly did not obey…in the days of Noah. The text in 1 Enoch, however, does specifically connect the Flood to the punishment of the Watchers and the evil acts of their children, the Nephilim.

Here’s the key to understanding why this is in the Bible at all: The neighbors of the ancient Hebrews, especially the Amorites who lived in and near Canaan, apparently believed that these mighty men of old were the ancestors of their kings. The spirits of the Nephilim were called rapha—Rephaim. What’s more, texts discovered at the Amorite kingdom of Ugarit, only translated within the last fifty years, indicate that the Amorites venerated these entities, summoned them through necromancy rituals, and believed that their kings joined their assembly after death.

While the Bible names tribes called Rephaim in the Transjordan, lands that later became the kingdoms of Ammon, Moab, and Edom, in the time of Abraham (around 1850 BC), it appears that by the Exodus the Rephaim were believed to be spirits of the venerated dead—except for Og, king of Bashan, who was called the last “of the remnant of the Rephaim.”

Here is where we differ with some Christian researchers: We do not believe the Rephaim and Anakim encountered by the Israelites were literal blood descendants of the pre-Flood Nephilim. They were tribes who worshiped their spirits in the deluded belief that those demons were their heroic royal ancestors. So, when 1 Chronicles 20:4–8 and 2 Samuel 21:15–20 refer to Goliath and other Philistine “descendants of the giants” (yĕlîdê hārāpâ), it’s in the spiritual sense. These “sons of Rapha” were an elite warrior cult dedicated to the mighty men who were of old.

Likewise, the Anakim, who are identified with the Rephaim in the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua, appear to have been a class of pagan warrior kings rather than supernaturally big. Contrary to the popular explanation that anak means “long-necked,” it actually derives from a Greek word, anax (“god,” “hero,” or “master of the house”). “Anakim,” then, was a title roughly meaning “lords” or “rulers,” and the “sons of Anak” were a warrior elite who ruled the hill country of Judah and Israel.

Veneration of the dead among the ancient Amorites was an integral part of their culture. A monthly ritual called kispum summoned dead ancestors to a ritual meal, which we’ll describe in detail in a future article. The kispum took on greater importance when it came to their dead kings; while the dead were dangerous if they were unhappy, dead royals were especially menacing. They posed a threat to the ruler himself, and that was a problem that could affect the entire kingdom. Bedeviled kings weren’t just a threat to their families; everyone in the kingdom suffered when a ruler was tormented by angry spirits.

The standard practice in the ancient Near East was to perform the kispum rite twice a month for kings, usually on the 15th and 30th. As with the family kispum, long-dead rulers had to be called to the meal by name. Forgetting the dead meant their spirits were unsettled and thus unpredictable. Proper performance of the ritual was key to maintaining the health and stability of the realm.

Several fascinating texts from Ugarit are especially relevant to our discussion. Around 1200 BC, just before its destruction by the so-called Sea Peoples, Ugarit crowned its last king. A ritual text designated KTU 1.161 by scholars suggests that the ill-fated Ammurapi III, who was probably killed when his city was overrun, was crowned with a necromancy rite that summoned the spirits of his royal ancestors, the Rephaim.

You are summoned, O Rephaim of the earth,

You are invoked, O council of the Didanu!

Ulkn, the Raphi’, is summoned,

Trmn, the Raphi’, is summoned,

Sdn-w-rdn is summoned, Ṯr ‘llmn is summoned,

the Rephaim of old are summoned!

You are summoned, O Rephaim of the earth,

You are invoked, O council of the Didanu!

There is no question that these Rephaim are the same group called by that name in the Bible.

Sheol beneath is stirred up to meet you when you come; it rouses the shades [rephaim] to greet you, all who were leaders of the earth; it raises from their thrones all who were kings of the nations. (Isaiah 14:9)

The “shades”—Rephaim—were “leaders of the earth” and “kings of the nations,” the same way they are described in the Ugaritic texts.

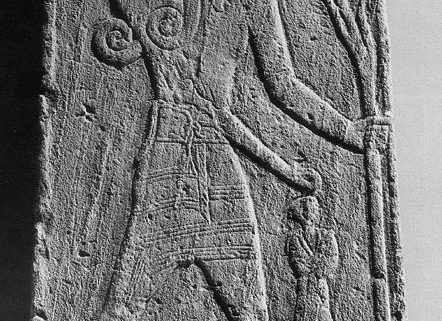

This appears to be a belief that extends back at least to the time of Abraham. A bone talisman dated to about 1750 BC found in the tomb of a king at Ebla, an ancient kingdom in northern Syria, depicting a scene that suggests three ranks in the hierarchy of the afterlife: A lower level for the human dead, a top level inhabited by the gods, and a middle level occupied by entities that probably represent the Rephaim. Scholars who have tried to interpret the symbols on the artifact believe the item was a guide for the spirit of the dead king on how to attain status among the venerated dead—the “men of renown,” as it were. Even the name “Rephaim” may originate with an Akkadian word that means something like “great ones.”

What ties this together into a cohesive package is a reference in the Ugaritic “Sacrifice of the Shades Liturgy” to the “council of the Didanu.” That shadowy group shares the name of an Amorite tribe from antiquity known and feared throughout the Near East, variously spelled Didanu, Ditanu, or Tidanu. The last Sumerian kings of Mesopotamia, the Third Dynasty of Ur, actually built a wall 175 miles long north of modern Baghdad that they dubbed the “Amorite Wall That Keeps Tidanu Away.”

Too bad for the Third Dynasty of Ur that it didn’t keep the Tidanu away. Within a century of the wall’s construction, Ur was overwhelmed by waves of invaders that included the Tidanu, savage Gutian tribesmen from the mountains to the northeast, and Elamites, from what is today northwestern Iran.

The key point is this: For centuries, Amorite kings from Babylon to Canaan traced their ancestry back to this Tidanu/Ditanu tribe. And modern scholars have concluded that the name of this tribe is the origin of the name given by the ancient Greeks to their old gods, the Titans.

Consider the evidence: We know that in the days of the judges in Israel, Amorite kings in what is now northern Syria aspired to become rapha and join the council of the Didanu after death, a religious belief that may have existed for more than a thousand years already by that time. The Rephaim were middle-tier deities, higher-ranking in the cosmic order than humans, but not at the level of the great gods like El, Baal, Asherah, and Astarte.

Like the Didanu, the Titans of the Greeks were supernatural inhabitants of the underworld who roamed the earth long ago, just like the apkallu of Babylon and the Watchers—the “sons of God” from Genesis 6—of the Hebrews. This is not a coincidence.

And it’s still relevant today. You see, the Rephaim Texts from ancient Ugarit call the Rephaim “warriors of Baal.” The mountain sacred to Baal is the rally point for the end-times army of Gog, the Antichrist—and Jesus identified Baal as Satan.

Veneration of the dead was not a quaint religious belief by primitive pagans who didn’t know any better. What we are unraveling here is an ancient plot by the infernal council to create a demonic army to assault the throne of God.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!