In the early 1970s, Kenneth Grant, personal secretary to Aleister Crowley twenty-five years earlier, broke with the American branch of Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis and formed his own Thelemic organization, the Typhonian O.T.O. The “Sirius/Set current” that Grant identified in the ‘50s referred to the Egyptian deity Set, god of the desert, storms, foreigners, violence, and chaos.

To grasp the significance of Grant’s innovation to Crowley’s religion, a brief history of Set is in order.

Set—sometimes called Seth, Sheth, or Sutekh—is one of the oldest gods in the Egyptian pantheon. There is evidence he was worshiped long before the pharaohs, in the pre-dynastic era called Naqada I, which may date as far back as 3750 BC. To put that into context, the Tower of Babel incident probably occurred toward the end of the Uruk period around 3100 BC. Writing wasn’t invented in Sumer until about 3000 BC, around the time of the first pharaoh, Narmer.

Set was originally one of the good gods. He protected Ra’s solar boat, defending it from the evil chaos serpent Apep (or Apophis), who tried to eat the sun every night as it dropped below the horizon. During the Second Intermediate Period, roughly 1750 BC to 1550 BC, Semitic people called the Hyksos, who were probably Amorites, equated Set with Baʿal, the Canaanite storm-god, and Baʿal-Set was the patron deity of Avaris, the Hyksos capital.

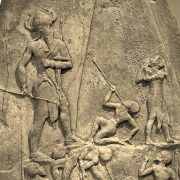

The worship of Baʿal-Set continued even after the Hyksos were driven out of Egypt. Two centuries after Moses led the Israelites to Canaan, three hundred years after the Hyksos expulsion, Ramesses the Great erected a memorial called the Year 400 Stela to honor the 400th year of Set’s arrival in Egypt. In fact, Ramesses’ father was named Seti, which literally means “man of Set.”

Set didn’t acquire his evil reputation until the Third Intermediate Period, during which Egypt was overrun by successive waves of foreign invaders. After being conquered by Nubia, Assyria, and Persia, one after another between 728 BC and 525 BC, the god of foreigners wasn’t welcome around the pyramids anymore. No longer was Set the mighty god who kept Apophis from eating the sun; now, Set was the evil god who murdered his brother, Osiris, and the sworn enemy of Osiris’ son, Horus.

By the time of Persia’s rise, Greek civilization was beginning to flower, and the Greeks identified Set with Typhon, the terrifying, powerful serpentine god of chaos. That’s the link between Set and Typhon. And this is the entity Kenneth Grant believed was the true source of power in Thelemic magick.

That’s why the “Sirius/Set current” led to the Typhonian O.T.O, and that’s the destructive, chaos-monster aspect of Set-Typhon we need to keep in view when analyzing the magickal system Grant created by filtering Crowley through the horror fiction of H. P. Lovecraft.

Grant’s anxiety, as expressed in Nightside of Eden and in his other works, is that the Earth is being infiltrated by a race of extraterrestrial beings who will cause tremendous changes to take place in our world. This statement is not to be taken quite as literally as it appears, for the “Earth” can be taken to mean our current level of conscious awareness, and extraterrestrial would mean simply “not of this current level of conscious awareness.” But the potential for danger is there, and Grant’s work— like Lovecraft’s—is an attempt to warn us of the impending (potentially dramatic) alterations in our physical, mental and emotional states due to powerful influences from “outside.”

Lovecraft died in 1937, but his work found a new audience in the 1970s. His stories were mined as source material by Hollywood. Then in 1977, a hardback edition of the Necronomicon, which Lovecraft invented as a plot device for his horror fiction, suddenly appeared (published in a limited run of 666 copies!), edited by a mysterious figure known only as “Simon,” purportedly a bishop in the Eastern Orthodox Church. According to Simon, two monks from his denomination had stolen a copy of the actual Necronomicon in one of the most daring and dangerous book thefts in history.

A mass market paperback edition followed a few years later. That version has reportedly sold more than a million copies over the last four decades. Kenneth Grant, who believed that Crowley and Lovecraft had been inspired or guided by the same supernatural source, validated the text, going so far as to offer explanations for apparent discrepancies between Crowley and the Necronomicon.

Crowley admitted to not having heard correctly certain words during the transmission of Liber L, and it is probable that he misheard the word Tutulu. It may have been Kutulu, in which case it would be identical phonetically, but not qabalistically, with Cthulhu. The [Simon] Necronomicon (Introduction, p. xix) suggests a relationship between Kutulu and Cutha…

Simon’s Necronomicon was just one of several grimoires (books of magic spells) published in the 1970s that claimed to be the nefarious book. The others were either obvious fakes published for entertainment purposes, or hoaxes that their authors admitted to soon after publication. Simon, on the other hand, appeared to be serious. But people involved with producing the “Simonomicon” have since admitted to making it up, and the central figure behind the book’s publication was Peter Levenda—author of The Dark Lord, the book documenting the highly improbable “coincidences” connecting Aleister Crowley and H. P. Lovecraft.

The text itself was Levenda’s creation, a synthesis of Sumerian and later Babylonian myths and texts peppered with names of entities from H. P. Lovecraft’s notorious and enormously popular Cthulhu stories. Levenda seems to have drawn heavily on the works of Samuel Noah Kramer for the Sumerian, and almost certainly spent a great deal of time at the University of Pennsylvania library researching the thing. Structurally, the text was modeled on the wiccan Book of Shadows and the Goetia, a grimoire of doubtful authenticity itself dating from the late Middle Ages.

“Simon” was also Levenda’s creation. He cultivated an elusive, secretive persona, giving him a fantastic and blatantly implausible line of [BS] to cover the book’s origins. He had no telephone. He always wore business suits, in stark contrast to the flamboyant Renaissance fair, proto-goth costuming that dominated the scene.

In The Dark Lord, Levenda not only analyzed Kenneth Grant’s magickal system and documented synchronicities between Crowley and Lovecraft, he validated the supernatural authenticity of the fake Necronomicon that he created!

But make no mistake—this doesn’t mean the Necronomicon is fake in the supernatural sense.

[W]e can conclude that the hoax Necronomicons—at least the Hay-Wilson-Langford-Turner and Simon versions—falsely claim to be the work of the mad Arab Abdul Alhazred; but in so falsely attributing themselves, they signal their genuine inclusion in the grimoire genre. The misattribution is the mark of their genre, and their very falsity is the condition of their genuineness. The hoax Necronomicons are every bit as “authentic” as the Lesser Key of Solomon or the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses.

In other words, while the published editions of the Necronomicon were obviously invented long after the deaths of H. P. Lovecraft and Aleister Crowley, they are still genuine tools for practicing sorcery. And, as Grant and Levenda suggest, they share a common origin in the spirit realm.

Simon’s Necronomicon arrived on the wave of a renewed interest in the occult that washed over the Western world in the 1960s and ‘70s. Interestingly, it was a French journal of science fiction that helped spark the revival, and it did so by publishing the works of H. P. Lovecraft for a new audience.

Planète was launched in the early ‘60s by Louis Pauwles and Jacques Bergier, and their magazine brought a new legion of admirers to the “bent genius.” More significantly for our study here, however, was the book Pauwles and Bergier co-authored in 1960, Les matins des magiciens (Morning of the Magicians), which was translated into English in 1963 as Dawn of Magic.

From Lovecraft, Bergier and Pauwles borrowed the one thought that would be of more importance than any other in their book. As we have seen, Morning of the Magicians speculates that extraterrestrial beings may be responsible for the rise of the human race and the development of its culture, a theme Lovecraft invented (emphasis mine).

The success of Pauwles and Bergier inspired others to run with the concepts they’d developed from the writings of Lovecraft. The most successful of these, without question, is Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods?

You can say one thing at least for von Däniken: He wasn’t shy about challenging accepted history.

I claim that our forefathers received visits from the universe in the remote past, even though I do not yet know who these extraterrestrial intelligences were or from which planet they came. I nevertheless proclaim that these “strangers” annihilated part of mankind existing at the time and produced a new, perhaps the first, homo sapiens.

The book had the good fortune of being published in 1968, the same year Stanley Kubrick’s epic adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey hit theaters. The film, based on the idea that advanced alien technology had guided human evolution, was the top-grossing film of the year, and was named the “greatest sci-fi film of all time” in 2002 by the Online Film Critics Society. By 1971, when Chariots of the Gods? finally appeared in American bookstores, NASA had put men on the moon three times and the public was fully primed for what von Däniken was selling.

It’s hard to overstate the impact Chariots of the Gods has had on the UFO research community and the worldviews of millions of people around the world over the last half century. In 1973, Twilight Zone creator Rod Serling built a documentary around Chariots titled In Search of Ancient Astronauts, which featured astronomer Carl Sagan and Wernher von Braun, architect of the Saturn V rocket. The following year, a feature film with the same title as the book was released to theaters. By the turn of the 21st century, von Däniken had sold more than 60 million copies of his twenty-six books, all promoting the idea that our creators came from the stars.

To this day, von Däniken’s book is the best-selling English language archaeology book of all time. Is it any wonder that more Americans believe that we’ve been visited by ET than in God as He’s revealed Himself in the Bible?

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!