The divine rebel in Eden, the nachash of Genesis 3, is called a “guardian cherub” in Ezekiel 28. As we showed you in a previous article, nachash and saraph, the singular form of seraphim, are interchangeable terms. But if the rebel in Eden was one of the seraphim, how could he also be one of the cherubim? Good question.

Cherubim are mentioned more frequently than the seraphim in the Old Testament. They are usually referenced in descriptions of the mercy seat on top of the Ark of the Testimony (Ark of the Covenant) and in reference to carved decorations in Solomon’s Temple. Two exceptions are the cherubim who guard the entrance to Eden and the four cherubim Ezekiel saw in his famous “wheel within a wheel” vision by the Chebar canal.

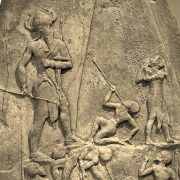

Most of us today have a mental image of cherubim that was shaped by artists in the Middle Ages—cute, chubby little boys with tiny wings who filled up the empty space in religious paintings. Nothing could be farther from the biblical and archaeological truth. Cherubim are scary, dangerous creatures we do not want to mess with.

The cherubim of the mercy seat are usually shown as a matched pair of plainly recognizable angels perched on top of the Ark of the Covenant with their outstretched wings touching in the middle. The Bible doesn’t describe them other than mentioning their wings and faces. Why? Because everybody in the fifteenth century BC knew what a cherub looked like, and they knew it was right and proper for them to serve as Yahweh’s throne-bearers. You see, God appeared to men above the mercy seat “enthroned on the cherubim.”

But the cherubim Ezekiel saw looked like something from a nightmare:

…this was their appearance: they had a human likeness, but each had four faces, and each of them had four wings. Their legs were straight, and the soles of their feet were like the sole of a calf’s foot. And they sparkled like burnished bronze.

Under their wings on their four sides they had human hands. And the four had their faces and their wings thus: their wings touched one another. Each one of them went straight forward, without turning as they went.

As for the likeness of their faces, each had a human face. The four had the face of a lion on the right side, the four had the face of an ox on the left side, and the four had the face of an eagle.

Such were their faces. And their wings were spread out above. Each creature had two wings, each of which touched the wing of another, while two covered their bodies. And each went straight forward. Wherever the spirit would go, they went, without turning as they went.

As for the likeness of the living creatures, their appearance was like burning coals of fire, like the appearance of torches moving to and fro among the living creatures. And the fire was bright, and out of the fire went forth lightning.

And the living creatures darted to and fro, like the appearance of a flash of lightning. (Ezekiel 1:5–14; emphasis added)

While these living creatures aren’t identified as cherubim in these verses, they are specifically called cherubim in Ezekiel 10—and we’ll see them again in the throne room of God when we get to the book of Revelation.

And every one had four faces: the first face was the face of the cherub, and the second face was a human face, and the third the face of a lion, and the fourth the face of an eagle. (Ezekiel 10:14)

Did you notice that the prophet saw a cherub instead of an ox for the fourth face? Is there some connection between the cherub and the ox?

Actually, yes.

The word “cherub” probably comes from the Akkadian karibu (the “ch” should be a hard “k” sound). It means “intercessor” or “one who prays.” The karibu were usually portrayed as winged bulls with human faces, and huge statues of the karibu were set up as divine guardians at the entrances of palaces and temples. This is the role of the cherubim “at the east of the garden of Eden…to guard the way to the tree of life.”

Cherubim were the gold standard for guarding royalty in the ancient Near East. In Assyria they were called lamassu, and the Akkadians called them shedu. They were sometimes depicted as winged lions rather than bulls, and they were often incorporated into the thrones of kings. So, the function of the biblical cherubim, guarding the tree of life and carrying the throne of God, was entirely consistent with what the neighbors of the Israelites knew about these beings. Based on what archaeologists have found in the Levant (modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel), the cherub was more like a winged, bull-like sphinx than a humanoid with wings.

The presence of cherubim in the Bible isn’t an accident or an invention of the Hebrew prophets. The cherubim were known by different names by the other cultures of the ancient Near East, but they served a similar role in all of them. They were supernatural bodyguards for the throne of Yahweh, and their imagery was appropriated by earthly kings.

So, we’ve identified, as best we can, the nachash, one of the entities—gods, if you will—who was a member of the assembly on God’s holy mountain. But what about the other gods? Who else was in Eden with God, Adam, Eve, and the nachash? What do we know about them?

More than you’d think. Unfortunately for us, English doesn’t convey the full sense of the Hebrew words that describe the supernatural beings in the Bible. For example, our English word “angel” covers a range of entities—cherubim, seraphim, ophanim, malakim, bene elohim, and others in Hebrew, as well as archangels and Watchers. That’s made it easier for scholars and theologians to get around the idea that multiple gods are clearly described in the Bible.

We know those gods were in the Garden, or Yahweh would not have inspired Ezekiel to call Eden “the seat of the gods.” And it’s possible they’re mentioned in Ezekiel 28, just not in the way we expect.

Scholars generally agree that Ezekiel 28 is linked to Isaiah 14, another account of the divine rebel being tossed out of Eden:

How you are fallen from heaven,

O Day Star, son of Dawn!

How you are cut down to the ground,

you who laid the nations low!

You said in your heart,

“I will ascend to heaven;

above the stars of God

I will set my throne on high;

I will sit on the mount of assembly

in the far reaches of the north.” (Isaiah 14:12–13)

Ezekiel 28 and Isaiah 14 describe the same event, so we have confirmation of other divine beings in Eden. In the Ezekiel account, God describes how the “anointed guardian cherub” was cast out of Eden, where he’d once walked “in the midst of the stones of fire.” Compare that with what we discussed above about the brazen, glowing, or burning appearance of the beings encountered by Moses, Daniel, and Isaiah. And in Psalm 104:4, we read that God “makes his messengers winds, His ministers a flaming fire.”

In the Isaiah 14 passage above, we also see a reference to the “stars of God.” Scholars agree that “stars” in the Old Testament often refer to the bene ha’elohim (“sons of God”). For example, when Yahweh rebuked Job for his lack of faith:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell me, if you have understanding.

Who determined its measurements—surely you know!

Or who stretched the line upon it?

On what were its bases sunk,

or who laid its cornerstone,

when the morning stars sang together

and all the sons of God shouted for joy? (Job 38:4–7; emphasis added)

The divine rebel in Eden was cast out of the Garden and the divine council for his pride and his desire to set his throne “above the stars of God”—sons of God who appear as beings of fire and light. If we read the passages in Ezekiel 28 and Isaiah 14 as consistent with one another, then the “stones of fire” in Eden were the sons of God that the nachash wanted to rule from his own “mount of assembly in the far reaches of the north.”

Bible teachers often de-supernaturalize the puzzling references to fiery, flying serpents by offering naturalistic explanations. Some suggest that the fiery serpents of Numbers 21 were saw-scaled vipers, dangerous venomous snakes native to the Sinai Peninsula. Others claim that the verses are proof that dragons or pterodactyls were alive during the Exodus. Both suggestions miss the point. We need to keep our eyes on the supernatural.

Well, the consequences of the rebellion in Eden were immediate and harsh:

The Lord God said to the serpent, “Because you have done this, cursed are you above all livestock and above all beasts of the field; on your belly you shall go, and dust you shall eat all the days of your life.

I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.”…

Then the Lord God said, “Behold, the man has become like one of us in knowing good and evil. Now, lest he reach out his hand and take also of the tree of life and eat, and live forever—”

Therefore the Lord God sent him out from the garden of Eden to work the ground from which he was taken. He drove out the man, and at the east of the garden of Eden he placed the cherubim and a flaming sword that turned every way to guard the way to the tree of life. (Genesis 3:14–15, 22–24)

Well-meaning Christians for generations have pointed to Genesis 3:14 as the moment in history when snakes lost their legs. Again, that misses the point. God didn’t remove the legs of snakes; He described the punishment of the nachash in figurative language. You don’t need to be a biologist to know that snakes do not eat dust.

What happened was this: The nachash was cast down from the peak of the supernatural realm, “full of wisdom and perfect in beauty,” to be the lord of the dead. What a comedown! Isaiah 14 makes a lot more sense when you keep a supernatural worldview in mind:

Sheol beneath is stirred up

to meet you when you come;

it rouses the shades to greet you,

all who were leaders of the earth;

it raises from their thrones

all who were kings of the nations.

All of them will answer

and say to you:

“You too have become as weak as we!

You have become like us!” (Isaiah 14:9–10)

Refer to our previous book, Veneration, for a deep dive into the significance of those verses. The “shades” Isaiah mentioned were the Rephaim (root word rapha), divinized royal ancestors of the pagan Amorites who surrounded ancient Israel. Moses did not invent the Rephaim when he wrote the Pentateuch. They were well known to their neighbors, and their worship was a central part of the lives of the pagans of the ancient Near East.

For Adam and Eve, the banishment affected the two of them and all their descendants through the present day. Instead of living with God as members of His council, we humans have struggled for millennia to make sense of a world that often seems to make no sense. The memory of our brief time in the Garden of God has echoed down through the long and many centuries since, and it may be the source of our belief that mountains are somehow special: reserved for the gods.

Eden was a lush, well-watered area “on the holy mountain of God,” where Yahweh presided over His divine council. The council included the first humans along with the loyal elohim (those who had not sided with Chaos during that first rebellion). Adam and Eve walked and talked with the supernatural “sons of God” who (based on clues scattered throughout the Bible) were beautiful, radiant beings.

And, at least some of them were serpentine in appearance.

So, back to the question: How could the divine rebel be both a nachash and a cherub? There are two possible answers.

First, the Septuagint translation, prepared by Jewish religious scholars about two hundred years before the birth of Jesus, interpreted Ezekiel 28 as reading that the divine rebel was placed in Eden with the guardian cherub, who then ejected the rebel from the Garden for his sin. The Jewish translators worked with older copies of the Hebrew scriptures than are available today, so it’s possible that the chapter was changed by the time the Masoretic Hebrew text, on which are English Old Testament is based, was completed around 1000 AD. If this is true, then the nachash—Satan—was tossed out of Eden by the guardian cherub and there’s no contradiction.

The second possibility is one I suggest in my new book, The Second Coming of Saturn: If the rebel described in Ezekiel 28 and Isaiah 14 was a fallen angel other than Satan, then he may not have been a nachash at all. Again, the contradiction disappears.

I believe that’s the correct answer, but there is no space here to make that case. That will have to wait for a future article.

The bottom line is this: A long war has raged between Yahweh and the sons of God who rebelled. This conflict is not just about control of the spirit realm, it’s also about whether humanity will be restored to its rightful place “in the seat of the gods”—among the divine council on the holy mountain of God. We see God’s battle plans and references to previous skirmishes in the Bible, but a day is coming when He will destroy all enemies.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!