The ancient Amorite tribe called the Tidanum was not only honored by their descendants, it was venerated. Based on texts found across the ancient Near East, the Tidanum were the ancestors of the ruling houses of the old Assyrian kingdom of Šamši-Adad, the old Babylonian empire of Hammurabi the Great, and the kings who ruled Ugarit down to about 1200 B.C. Two of the kings in the line of Hammurabi include a variant of the tribal name as the theophoric element (Ammi-ditana and Samsu-ditana), indicating that the Tidanum, if not gods, were at least considered god-like by their descendants.

The name Tidanum and its variants—Tidinu, Titinu, Tidnim, Didanum, Ditanu, Datnim, Datnam—had a strong military connotation in ancient Mesopotamia. A text from Ebla refers to an official named Tidinu, chief of the mercenaries in the court of Ibrium, the powerful vizier of king Irkab-damu in the 24th century B.C. It appears that some Amorites served Sumerian kings during the late 3rd millennium B.C. as soldiers, and they might even have been part of the royal bodyguard in Ur for kings Shulgi and Šu-shin.

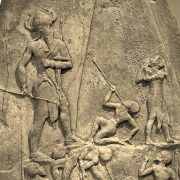

But the Tidanum were also depicted as enemies of Sumer alongside Anshan (northwest Iran) by Shulgi, who ruled Ur for nearly half a century sometime around 2100 B.C. His son, Šu-sin, marked one of the years of his reign as the year in which he defeated a coalition of rebellious Tidnum and Ya’madium, another Amorite tribe that lived in eastern Mesopotamia.

And when Ur finally fell around 2004 B.C., the “Tidnumites” were one of the groups blamed in a Lamentation Over the Destruction of Sumer and Ur:

In Ur, no one took charge of food, no one took charge of water,

Who was (formerly) in charge of food, stood away from the food, pays no heed to it,

Who was (formerly) in charge of water, stood away from the water, pays no heed to it,

Below, the Elamites are in charge, slaughter follows in their wake,

Above, the Halma-people, the “men of the mountains,” took captives,

The Tidnumites daily fastened the mace to their loins…1

So what’s the significance of the Tidnum/Tidanu? We’ll get to that shortly.

After the fall of Ur, things changed quickly. Scholars still debate whether the change was by conquest or gradual assimilation, but within a hundred years or so Amorites had taken control of every major political entity from Canaan to southern Mesopotamia.

A hundred years after that, by the early 18th century B.C., an Amorite city-state that had been a small settlement on the Euphrates since about 2300 B.C. began an incredible rise to become the dominant power in Mesopotamia—Babylon. It became so influential that people from the time of Isaac and Jacob until the present day have called the region Babylonia instead of Sumer.

Take a moment and think back to Genesis 15:16: “The iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete.”

Now realize that Babylon, a byword for sin, depravity, and occult wickedness throughout the Bible, even in prophecy that is yet to be fulfilled, was founded by the Amorites.

There is no ethnicity called “Babylonian.” That’s like me claiming to be ethnically Chicagoan (Chicagoite?) because I was born there. Babylon was just the name of a small village led by an ambitious Amorite chief named Sumu-Abum. He and his next few successors didn’t even bother calling themselves “king of Babylon,” an indication of how unimportant it was at first. It was more than a hundred years before Hammurabi, the greatest Amorite king in history, made Babylon a regional power.

As with all cities in Mesopotamia, the village of Babylon had a patron god. Marduk was a second-rate member of the pantheon until the Amorites elevated Babylon to prominence during the 18th century B.C. By the second half of the 2nd millennium B.C., Marduk had assumed the top position in the Mesopotamian pantheon, replacing Enlil as king of the gods.

Marduk’s early character is obscure. As Babylon grew in importance, the god assumed traits of other members of the pantheon, especially Enlil and Ea (the Akkadian name for Enki). Marduk was considered the god of water, vegetation, judgment, and magic. He was the son of Ea and the goddess Damkina, and his own consort was Sarpanit, a mother goddess sometimes associated with the planet Venus, and not surprisingly, the goddess Ishtar/Inanna.

By the time of the Exodus, Babylon had been the dominant power in Mesopotamia for nearly three hundred years. It proudly carried on the tradition of arcane pre-flood knowledge brought to mankind by the apkallu, who, as fish-men from the abzu, were presumably able to survive the flood, or by Gilgamesh, who is mentioned on a cylinder seal as “master of the apkallu.”

Of course, the Hebrews under Moses knew that the knowledge of the apkallu/Watchers was forbidden, secrets that humans weren’t meant to know. It was as much the reason for the imprisonment of the Watchers as their sexual sin of mating with human women. And this knowledge was proudly celebrated by the Amorite kings and priests of Babylon.

Bringing this back around to the conquest of Canaan: That’s why the kingdoms of Sihon of Heshbon and Og of Bashan were charam, a Hebrew word usually translated in the Old Testament “devoted to destruction.” It was applied to people and things that were spiritually irredeemable. And that’s why Moses went out of his way to show his readers the connection between the Amorites of Babylon and the Amorites of the Promised Land.

How did he do that? Have you ever wondered why Moses bothered to include this little detail in his account of the victory over Og?

For only Og the king of Bashan was left of the remnant of the Rephaim. Behold, his bed was a bed of iron. Is it not in Rabbah of the Ammonites? Nine cubits was its length, and four cubits its breadth, according to the common cubit.

Deuteronomy 3:8-11 (ESV), emphasis added

Nine cubits by four cubits is thirteen-and-a-half feet by six feet! So Og was a giant, right? Well… No, not necessarily.

Yes, the Rephaim were linked to the Anakim, the descendants of the Nephilim, and tradition holds that Og was a really big dude. But that wasn’t the point here. Moses was writing to an audience that was familiar with the infamous occult practices of Babylon.

Every year at the first new moon after the spring equinox, Babylon held a new year festival called the akitu. It was a twelve-day celebration of the cycle of regeneration, the beginning of a new planting season, and it included a commemoration of Marduk’s victory over Tiamat. The entire celebration, from Yahweh’s perspective, was a long ritual for “new gods that had come recently” involving all manner of licentious behavior.

The highlight of the festival was the Divine Union or Sacred Marriage, where Marduk and his consort, Sarpanit, retired to the cult bed inside the Etemenanki, the House of the Foundation of Heaven and Earth, the great ziggurat of Babylon. Although scholars still debate whether the Sacred Marriage was actually performed by the king and a priestess, it didn’t matter to Yahweh. The idea that a bountiful harvest in the coming year depended on celebrating Marduk’s sacred roll in the sack was abhorrent.

Now, here’s the key point: Guess how big Marduk’s bed was?

“…nine cubits [its long] side, four cubits [its] front, the bed; the throne in front of the bed”.2

Nine cubits by four cubits. Precisely the same dimensions as the bed of Og. That is why Moses included that curious detail! It wasn’t a reference to Og’s height; Moses was making sure his readers understood that the Amorite king Og, like the Amorite kings of Babylon, was carrying on pre-flood occult traditions brought to earth by the Watchers.

And that’s why Og and his Amorite ally Sihon were charam. The term is used multiple times in the Old Testament, especially about the Amorites and their allies in the Book of Joshua. It was, and still is today, a spiritual battle.

But that’s not all. Oh, no—there’s a lot more we can add to the legacy of the Amorites. Let’s go back to our discussion of that fearsome tribe, the Tidanu.

A scholar named Amar Annus made a startling connection in 1999 that has gone mainly unnoticed, especially by Bible scholars. Several Amorite royal houses, including those of the old Babylonian kingdom, the old Assyrian kingdom, and the kings of Ugarit, traced their ancestry from Dedan, whose descendants were called the Didanu, Tidanum, and variations thereof.

According to Annus, that’s the name from which the Greeks derived the one they gave to their old gods: Titanes—the Titans.3

Did Amorite royalty really believe they descended from the Titans, the old gods who had been banished to Tartarus, a special level of the underworld reserved for supernatural threats to the divine order? Yes, it looks that way.

Given the established links between the Amorites/Canaanites, the Rephaim/Nephilim, the Titans/Watchers, and the forbidden pre-flood knowledge brought back into the world by the Amorite kingdom of Babylon, this speculation isn’t exactly coming out of thin air.

1 Pritchard, James B., editor. 1958. The Ancient Near East: Volume I, An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, p. 616. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

2 Veijola, Timo. “King Og’s Iron Bed (Deut 3:11): Once Again,” Studies in the Hebrew Bible, Qumran, and the Septuagint (ed. Peter W. Flint et al.; VTSup 101; Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2003) p. 63.

3 Annus, Amar. “Are There Greek Rephaim? On the Etymology of Greek Meropes and Titanes,” Ugarit-Forschungen 31 (1999), pp. 13-30.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!