Dagan, father-god of the Amorites who lived along the Euphrates River in what is Syria

today, was Enlil and El by a different name. You’ve probably noticed the similarity between the

name of this god and Dagon, chief god of the Philistines. You’re right, they’re one and the same.

Over the thousand-plus years between the oldest texts that mention Dagan in Syria and the story

of Samson in the Book of Judges, the pronunciation changed a little. The last “a” sound shifted

to an “o,” not an unusual change.

But since the worship of Dagan isn’t recorded anywhere in ancient Israel (maybe because

the pagans there called him El), you may also be wondering how and when the Philistines

transplanted a god from the north of Syria to the Gaza strip. Good question.

Archaeologists digging in the Amuq River valley in southern Turkey since the early

2000s have discovered evidence of a powerful early Iron Age state called Palistin (or Walistin),

which was based at a city called Kunalua about fifteen miles southeast of Antioch. This may be

the Calneh or Calno mentioned twice in the Bible (Amos 6:2, Isaiah 10:9). 1 Palistin emerged

after the Bronze Age collapse around 1200 BC, when the Hittite Empire in Anatolia was

destroyed along with most of the kingdoms in the eastern Mediterranean. This new state survived

from the eleventh century BC down to about 700 BC, roughly from the time of Samuel and Saul

to the time of Isaiah and Hezekiah.

Scholars first assumed that the eleventh century BC pottery they found at Kunalua was

Aegean—the Greeks or their cousins. However, some are rethinking that theory and concluding

that the pots were local copies of styles “not of Greece but rather of Cyprus and south-west Asia

Minor.” 2 That means these people weren’t invaders, but descendants of the survivors of the chaos

and destruction of the Bronze Age collapse. In other words, the kingdom of Palistin was

probably founded by people who probably knew and worshiped Dagan all along.

You’ve surely also noticed the similarity between “Palistin,” “Philistine,” and

“Palestine.” Again, you are correct—scholars are certain it’s the same name. So, how did they

get from around the border between Turkey and Syria down to Gaza, on the boundary with

Egypt?

Egyptian records document several battles with the Sea Peoples between about 1200 and

1150 BC. This coalition included groups the Egyptians called the Ekwesh, Denyen, Sherden

(probably Sardinians), Weshesh, and finally the Peleset, who were almost certainly the

Philistines. Scholars have assumed that these battles took place near the Egyptian homeland and

that the defeated Philistine invaders were settled along the coast in Canaan in the cities that

became infamous in the Old Testament—Gaza, Gath, Ashdod, Ekron, and Ashkelon.

But some scholars have been rethinking this recently, placing those battles in what is now

Syria rather than in Egypt:

1. The land battles between Egypt and the “Sea-Peoples” occurred along

the northern frontiers of the Egyptian empire in the Levant.

2. The naval clashes were most likely raids on the prosperous Egyptian

cities of the Nile Delta.

3. The “Sea-Peoples” were essentially north Levantine (including western

Anatolian) populations known as former allies of the Hittites.

4. There is no textual or archaeological evidence that Philistines were ever

settled by the Egyptians in Canaan. There is, however, evidence of their

settlement in Egypt and in Syria soon after the battles.

5. Some of those “Sea-Peoples” established the kingdom of Palistin in the

‘Amuq Plain. Others reached Philistia, probably by sea, as Egyptian rule over the

Levant deteriorated. 3

Not only does this explain how worshipers of Dagan got from northern Syria to the

territory of the Philistines on the border of Egypt, it also IDs the kingdom of Palistin as the

mostly likely place where the Hittite and Hurrian myths of Kumarbi, “he of Kumar” (the city

near Aleppo, which was part of the territory ruled by Palistin), were transmitted to Cyprus and

western Asia Minor, where, over the course of several hundred years, they were transformed into

stories of the Greek Titan, Kronos. 4

It’s important to remember that there is little we can know for sure about the entity who

wore all these names. In fact, it’s possible that more than one interacted with our distant

ancestors under one or more of these identities. We humans do not see clearly into the spirit

realm, and besides, these entities have been lying to us since the beginning. The best we can do

is try to discern patterns without getting hung up on fine details. As Shakespeare wrote, “that

way madness lies.”

Utter disregard for human life and a connection to the underworld are recurring themes

with Enlil/El/Dagan, etc. In ancient Sumer, Enlil was the one who decided that creating

humankind was a mistake because our noise kept him awake at night. His solution was the global

flood, which the Sumerians recorded in their king lists. According to the Epic of Atrahasis,

named for the Sumerian Noah, humanity was saved by the intervention of the crafty god Enki,

lord of the abzu (“abyss”), who disobeyed the command of Enlil and warned his faithful

worshiper, Atrahasis, of the genocide decreed by Enlil. 5

Make sure you register that deception: The ancient Mesopotamians believed that the lord

of the abyss saved humanity from the Flood.

In general, “the” god was considered a cold, distant entity who had to be appeased

through sacrifice—often the human variety. This is a well-documented aspect of Baal-Hammon

and Kronos. The tophets excavated at Carthage and other Phoenician sites around the

Mediterranean have yielded the remains of literally thousands of infants and young children who

did not die of natural causes.

Saturn is best known as the god behind the Roman winter festival called Saturnalia,

which featured role reversals and a loosening of social norms. For example, masters would wait

on slaves, who were allowed to disrespect their owners; courts and schools were closed; people

wore clothing normally considered gauche; and most work was suspended for the duration of the

holiday.

But Saturn, like his counterparts, had a dark side. The fourth-century Roman poet

Ausonius suggested that Saturn received dead gladiators as offerings during his festival, 6 a claim

echoed by Macrobius, writing two generations later, in his Saturnalia. 7

Because you’re a logical thinker, you won’t be surprised to learn that the Saturnalia was

based on an earlier Greek holiday called the Kronia, so named for his Greek equivalent Kronos,

which was celebrated in mid to late summer. Sacrifices of adult humans to Kronos are attested on

the islands of Crete and Rhodes, 8 and he was identified as the Greek equivalent of the Phoenician

god Baal-Hammon. As we noted earlier, his name probably means “lord of the Amanus

(mountains),” 9 referring to a range in southern Turkey near Mount Zaphon (today called Jebel al-

Aqra), the mountain sacred to Baal. This and evidence from southern Turkey of a festival that

appears to be a forerunner of the Kronia 10 are solid evidence that the veneration of Kronos began

closer to Mesopotamia than to Greece.

The similarity of “the” god’s struggles with his father, Ouranos/Anu, and son

Zeus/Teshub (the Hurrian storm-god), make the equation Kronos = Kumarbi a sure thing. Here

we come full circle, as the Hurrian god Kumarbi was identified in the ancient world as Dagan,

chief god of the middle Euphrates region, and Enlil, king of the pantheon in ancient Sumer. 11

Nippur, the city sacred to Enlil in Sumerian religion, is named as Kumarbi’s home in the Hittite

myth called Kingship in Heaven or Song of Emergence. 12

Thus, Enlil was Kumarbi, Dagan, El, Kronos, Saturn, and Baal-Hammon.

Archaeologists have not documented human sacrifice in the worship of El, Dagan, and

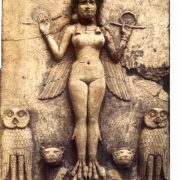

Kumarbi, but there are definite underworld connections for all three. For example, Dagan, chief

god of the lands along the Euphrates River in Syria, was called bēl pagrê, which has been

variously translated as “lord of corpse offerings, lord of corpses (a netherworld god), lord of

funerary offerings, and lord of human sacrifices.” 13 Kumarbi was one of the “primeval gods” of

the Hurrians, deities who’d once ruled the world but who, like the Titans of Greek myth, had

been banished to the netherworld by the storm-god. 14

Texts from the Amorite kingdom of Ugarit point to Mount Hermon as the abode of El,

and the connections between that mountain and the netherworld are well documented, as we’ve

already noted. Amorites in western Mesopotamia and the Levant believed El and his consort

Asherah held court on Mount Hermon along with their seventy sons.

Hermon is the northernmost point in Israel today, the border between the Jewish state,

Lebanon, and Syria. Below its southeastern slopes was Bashan, the kingdom of Og, called the

last of the remnant of the Rephaim. 15 Veneration of the Rephaim was a key element of Canaanite

religion, whose depiction in Ugaritic texts is consistent with their portrayal in the Bible as the

spirits of mighty kings of old. Careful reading of certain passages of the Bible, especially Isaiah

14:9–21, Ezekiel 32:27, and Ezekiel 39:11, shows that the prophets surely knew of the Rephaim.

Their condemnation of those spirits and the veneration thereof is clear.

As mentioned earlier, a god named Rapiu, the singular form of “Rephaim,” was believed

to rule at Ashtaroth and Edrei, the same two cities named in the Bible as the seats of Og’s

kingdom. Ugaritic religious texts also connect Ashtaroth to the god Molech, further supporting

the identity of Bashan as an evil place.

This also gives new meaning to the phrase “bulls of Bashan” in Psalm 22:12, a prophecy

of the Messiah suffering on the cross. Dr. Robert D. Miller II correctly observes that the term is

“not about famous cattle but about cultic practice.” In his 2014 paper, Miller used archaeology

and climatology to show that Bashan, contrary to what you may have heard, was a lousy place to

raise cattle three thousand years ago, concluding that “Bulls of Bashan refers not to the bovine

but to the divine.” 16

So, those bulls were not cattle but the spirits of the Rephaim and their masters, the fallen

angels who masqueraded as gods. It’s not a coincidence that bull imagery is connected to them in

the Bible: The Canaanite creator-god was called Bull El; the root word behind the name Kronos

likely means “horned one”; 17 and the name Titan, derived from the tribe named Ditanu or Tidanu,

probably originates with the Amorite ditanum, meaning “bison” or “aurochs.” 18

Then, on the southwest side of Hermon, we find Banias, better known as the Grotto of

Pan. This is the cave from which the waters of the Jordan emerged in ancient times. Pagans

venerated the site for centuries, and ancient historians wrote that sacrifices were tossed into the

waters of the cave where they were accepted by the god therein if the offerings sank.

Not to belabor the point, but the bottom line is that Hermon, El’s mount of assembly,

towered over the entrance to the underworld.

Alone among these entities, El of the Canaanite pantheon seemed to deal with humanity

in a positive way. In the Legend of Keret, a text from Ugarit dated to about the period of the

judges in Israel, El personally intervened on behalf of a king who was distressed over the lack of

an heir. Interestingly, King Keret’s domain in the tale is called Hubur, which was the name of a

river that played a role in older Sumerian and Akkadian myths similar to that of the River Styx in

Greek cosmology—the border between the land of the living and the netherworld.

On the other hand, we must consider El’s favorites to take his place as king of the gods:

Yamm, the chaos-god of the sea, and Mot, the god of death. The storm-god Baal had to defeat

both in brutal combat to assume kingship. Since life-giving rain for crops, livestock, and our own

survival is far more welcome among us mortals than chaos or death, El’s favorites among the

gods reveal an inconsistent level of concern for his human creations, at the very least.

To summarize: “The” god of the ancient world was, for the most part, a distant, uncaring

entity, often linked to the underworld. At his worst, he demanded the sacrifice of humans,

including children, and, in the case of Enlil, was prepared to obliterate the entire human race just

for a good night’s sleep. His home, at various points in his career, was the Sumerian city Nippur,

the Amorite town Tuttul (near Raqqa in northern Syria), the Amanus mountains, Mount Hermon

on the northern border of Israel.

Finally, in the guise of Saturn, considered the founder of the Latin race, he settled in

west-central Italy, where Rome would eventually rise under the divine kingship of his son, the

storm-god, Jupiter.

1 “Calneh” in Genesis 10:10 may be a mistranslation of a Hebrew word meaning “all of

them,” resulting in the translation “all of them in the land of Shinar” (RSV). See W. A. Elwell &

B. J. Beitzel, B. J., “Calneh.” Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker

Book House, 1988), 405.

2 Shirly Ben-Dor Evian, “Ramesses III and the ‘Sea-Peoples’: Towards a New Philistine

Paradigm.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 36(3) (2017), 278.

3 Ibid.

4 Jenny Strauss Clay and Amir Gilan, “The Hittite ‘Song of Emergence’ and the

Theogony.” Philologus 58 (2014), 1–9.

5 “The Epic of Atrahasis.” Livius (http://www.livius.org/sources/content/anet/104-106-

the-epic-of-atrahasis/), retrieved 11/9/18.

6 Ausonius, Eclogue 23.

7 Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.7.31.

8 Jan N. Bremmer, The Strange World of Human Sacrifice. (Leuven: Peeters, 2007),

57–58. See also Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, XX. 14.4-7 (ed. Loeb).

9 Cross, op. cit., 26.

10 Jan N. Bremmer, “Remember the Titans!” In The Fall of the Angels, C. Auffarth and L.

Stuckenbruck, eds. (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2004), 46.

11 Alfonso Archi, “The West Hurrian Pantheon and Its Background.” In Beyond Hatti: A

Tribute to Gary Beckman, Billie Jean Collins and Piotr Michalowski (eds.) (Atlanta: Lockwood

Press, 2013), 12.

12 Ibid., 1.

13 Brian B. Schmidt, “Israel’s Beneficent Dead: The Origin and Character of Israelite

Ancestor Cults and Necromancy.” Doctoral thesis: University of Oxford (1991), 158–159.

14 Wyatt (2010), op. cit., 600.

15 Deuteronomy 3:11.

16 Robert D. Miller II, “Baals of Bashan.” Revue Biblique, Vol. 121, No. 4 (2014),

506–515.

17 Wyatt (2010), op. cit., 598.

18 Ibid., 595.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!