The Greeks and Romans shared a good deal of their religion. The names were different (with the notable exception of Apollo), but the gods were pretty much the same. Zeus of the Greeks was Jupiter of the Romans. Likewise, Aphrodite was Venus, Ares was Mars, Hera was Juno, Hephaestus was Vulcan, and so on.

Similarly, the old god of the Romans, Saturn, was the equivalent of Kronos, king of the Titans. In both Roman and Greek religion, this was the old god who ruled the earth during a long-ago Golden Age, when humanity lived like gods, free from toil and care. Both were overthrown by their son, the storm-god, and confined to the netherworld. To the Greeks, this was Tartarus, a place as far below Hades as the earth is below heaven; in Roman myth, Saturn was chained by Jupiter to ensure that he didn’t overeat. It was believed that Saturn consumed the passing days, months, and years. It obviously would have been a problem if the old god had turned his voracious appetite to consuming the present and future as well.

The most famous of the Roman religious festivals, Saturnalia, was adapted from the Kronia celebrated in the Greek world. The Kronia is first recorded in Ionia, the central part of western Anatolia (modern Turkey) in the eighth century BC, roughly the time of Isaiah. From there, the celebration spread to Athens and the island of Rhodes, and ultimately westward to Rome, although the festival shifted from midsummer to the winter solstice. Both festivals were a time of merriment and abandoning social norms, with gambling, gift-giving, the suspension of normal business, and slaves being served by their masters.

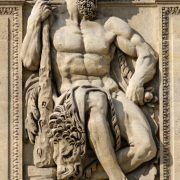

The annual party notwithstanding, the god had a darker side. It’s well documented that both Saturn and Kronos were connected to human sacrifice. Classical sources report that condemned prisoners were sacrificed to Kronos at Rhodes, children were offered to the god at Crete, and, as Baal-Hammon, the god was offered sacrifices of Phoenician children well into the Christian era. Perhaps most horrifying of all is the description of the first-century philosopher Plutarch.

[Carthaginians] offered up their own children, and those who had no children would buy little ones from poor people and cut their throats as if they were so many lambs or young birds; meanwhile the mother stood by without a tear or moan; but should she utter a single moan or let fall a single tear, she had to forfeit the money, and her child was sacrificed nevertheless; and the whole area before the statue was filled with a loud noise of flutes and drums took the cries of wailing should not reach the ears of the people.

Historians of the classical age made no distinction between Saturn, Kronos, and Baal-Hammon; to them, they were the same god worshiped under different names by Romans, Greeks, and Phoenicians. The parallel between child sacrifice and the myth of Saturn/Kronos devouring his own children to prevent their eventual rebellion is obvious. Diodorus Siculus, writing in the first century AD, drily noted that “the story passed down among the Greeks from ancient myth that Kronos did away with his own children appears to have been kept in mind among the Carthaginians through this observance.” Christian apologist Tertullian was less charitable:

Since Saturn did not spare his own children, of course he stuck to his habit of not sparing those of other people, whom indeed their own parents offered of themselves, being pleased to answer the call, and fondled the infants, lest they should weep when being sacrificed. And yet a parent’s murder of his child is far worse than simple homicide.

Indeed. In our modern, civilized world, we’ve mostly avoided the guilt associated with infanticide by convincing ourselves that an unborn child is simply a clump of cells that’s part of a pregnant woman’s body—heartbeat and unique DNA sequence notwithstanding.

We cannot lay the blame for the cult of Kronos, and the sacrifices offered later to his alter egos Saturn and Baal-Hammon, entirely on the Greeks. Careful reading of ancient texts reveals that this god is much older than the Greek civilization and originated farther east, in northern Mesopotamia. As at Saturnalia, the Kronia featured a reversal of normal social roles, most notably slaves served by their masters and eating with them at a common meal. It appears that this festival was very old by the time the Greeks established themselves as a world power.

A text discovered in 1983 at the site of the capital city of the Hittite kingdom, Hattuša, dated to about 1400 BC, the time of the Israelite conquest of Canaan, describes a myth in which the king of the gods, the storm-god Teshub (Baal/Zeus/Jupiter by a different name) has a ritual meal with the sun-goddess, Allani, and the “primeval gods” who’d been banished to the netherworld. Not only were the old gods at the table; they sat in the place of honor at Teshub’s right hand.

The celebration of the temporary suspension of the cosmic order surely accompanied the temporary suspension of the social order on earth. In other words, the myth with the “primeval gods” will have been associated with a ritual of reversal between masters and slaves. Now the Titans were also called “the old gods,” old and/or dumb people were insulted as Kronoi, and Attic comedy used expressions such as “older than Kronos” and “older than Kronos and the Titans.” Evidently, the antiquity of this divine generation had become proverbial at a relatively early stage of the tradition. The Titans thus can be legitimately compared to the Hurrian “primeval” gods.

It’s no coincidence that, like Kronos and Saturn, the Hurrian-Hittite god Kumarbi became king of the gods for a while by castrating his father, the sky-god, and was in turn deposed by his son, the storm-god, called Teshub by the Hurrians and Tarhunz by the Hittites. In other words, Kumarbi, who was worshiped in what is now Turkey and northern Syria, was an older incarnation of Kronos/Saturn/Baal-Hammon.

West drew attention to the conceptual similarity of the (Hittite) “former gods” (karuilies siunes) with the Titans, called Προτεροι Θεοι in Theogony 424, 486. Both groups were confined to the underworld (with the apparent exceptions of Atlas and Prometheus), and as Zeus banished the Titans thither, so Tešup [Teshub] banished the karuilies siunes, commonly twelve in number, like the Titans. They were in turn identified with the Mesopotamian Anunnaki. These were confined by Marduk to the underworld, or at least some of them were (half the six hundred, Enuma Elish vi 39–47, see 41–44), where they were ruled over variously by Dagan or Shamash.

The evidence for the earliest traces of this god point to a Mesopotamian origin, not Greek. Specifically, the trail leads to northwest Mesopotamia, in the area of the Mediterranean coast along the border between modern Syria and Turkey.

But this goes farther back than the Hittites and Hurrians of Joshua’s day. Scholar Amar Annus, who has done some absolutely brilliant work tracing the Watchers back from Hebrew texts to older Mesopotamian sources, came to an astonishing conclusion when he dug into the origin of the name of the former gods of the Greeks, the Titans. Annus notes first the existence of an ancient, and by the time of the Judges in Israel, almost mythical Amorite tribe called the Tidanu or Ditanu. They had a bad reputation in Mesopotamia—uncivilized, warlike, and dangerous. In fact, they were so threatening to the last Sumerian kings of Mesopotamia, the Third Dynasty of Ur, that around 2037 BC they began building a wall 175 miles long north of modern Baghdad specifically to keep the Tidanu away. We know this because the Sumerians literally named it bàd martu muriq tidnim, the “Amorite Wall Which Keeps the Tidnum at a Distance.”

Annus notes that the name “Ti/Di-ta/da-nu(m)—most possibly ‘large animal; aurochs; strong, wild bovide’—is the name of the eponymic tribe.” Then he points out that this tribe was linked to the Rephaim in ritual texts at Ugarit, the Amorite city-state destroyed around 1200 BC.

Greatly exalted be Keret

In the midst of the rpum (Rephaim) of the earth

In the gathering of the assembly of the Ditanu

So, the Ditanu/Tidanu were linked to the Rephaim in mind and ritual among the ancient Amorites, who, you remember, considered the Rephaim to be the divinized ancestors of their kings. What’s more, this assembly was summoned in what can only be described as a necromancy ritual for the coronation of Ugarit’s last king, Ammurapi III.

You are summoned, O Rephaim of the earth,

You are invoked, O council of the Didanu!

Ulkn, the Raphi’, is summoned,

Trmn, the Raphi’, is summoned,

Sdn-w-rdn is summoned,

Ṯr ‘llmn is summoned,

the Rephaim of old are summoned!

You are summoned, O Rephaim of the earth,

You are invoked, O council of the Didanu!

This council or assembly was more than just a group of honored forefathers, like the framers of the Constitution. One text from Ugarit makes reference to ritual offerings for the temple of Didanu, and temples owed sacrifices are typically devoted to gods. It appears, then, that between the birth of Abraham, around 1950 BC, and the time of the judges, circa 1200 BC, the Tidanu/Ditanu were transformed from a scary tribe of Amorites named for a giant wild bull into divine beings connected to the Rephaim, who likewise disappeared from the earth (in physical form) during that period.

And the Tidanu/Ditanu are probably the origin of the name of the bad old gods of the Greeks.

Then it may not be overbold to assume that the Greek Titanes originates from the name of the semi-mythical warrior-tribe (in Ugarit) tdn—mythically related to the Rpum in the Ugarit, and once actually tied together with Biblical Rephaim in II Samuel 5:18-22, where we have in some manuscripts Hebrew rp’m rendered into LXX as Titanes.

So, the veneration of this group of ancient entities extends at least as far back as the time of the judges, and probably much further. But why would the Greeks choose the name of an Amorite tribe for the old gods confined to Tartarus? Was that tribe literally descended from the old gods—the rebellious “sons of God” in Genesis 6? In other words, were the Tidanu/Ditanu literally Nephilim?

We’ll explore that next month.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!