During the Exodus, one of the more unusual confrontations between the Hebrews faithful to Yahweh and those who preferred a more tolerant view of the pagan religions they encountered occurred in the plains of Moab, the fertile area northeast of the Dead Sea, across the Jordan from Jericho.

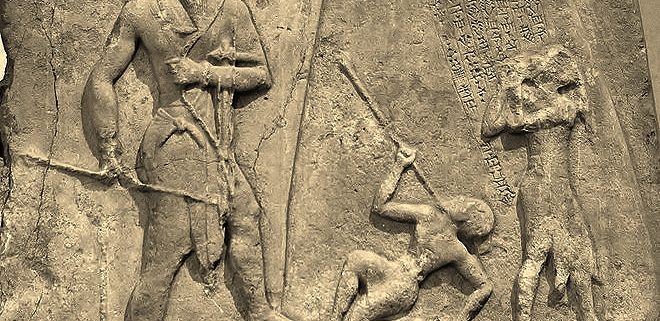

While Israel lived in Shittim, the people began to whore with the daughters of Moab. These invited the people to the sacrifices of their gods, and the people ate and bowed down to their gods. So Israel yoked himself to Baal of Peor. And the anger of the Lord was kindled against Israel. And the Lord said to Moses, “Take all the chiefs of the people and hang them in the sun before the Lord, that the fierce anger of the Lord may turn away from Israel.” And Moses said to the judges of Israel, “Each of you kill those of his men who have yoked themselves to Baal of Peor.”

And behold, one of the people of Israel came and brought a Midianite woman to his family, in the sight of Moses and in the sight of the whole congregation of the people of Israel, while they were weeping in the entrance of the tent of meeting. When Phinehas the son of Eleazar, son of Aaron the priest, saw it, he rose and left the congregation and took a spear in his hand and went after the man of Israel into the chamber and pierced both of them, the man of Israel and the woman through her belly. Thus the plague on the people of Israel was stopped. Nevertheless, those who died by the plague were twenty-four thousand. (Numbers 25:1–9)

This requires some unpacking. To our twenty-first-century minds, the reaction of Phinehas seems excessive. Today, many would call him out for his intolerance and accuse him of xenophobia, racism, or both. To atheists and skeptics, this story makes God out to be a monster since He obviously approved of Phinehas’ violent act. But that’s because most Americans today, especially those most likely to throw around that kind of epithet, view the world through a naturalistic bias. There is a lot here that’s only obvious if you understand what was happening in the spirit realm.

The first clue that there’s more to this story than is obvious at first read is the description of Phinehas’ killing stroke. Did you notice that he killed both the Israelite prince and the Midianite princess with one thrust of his spear? Without getting too graphic, there are only a couple of physical positions in which Phinehas could have speared them both with one jab.

There is other evidence in the text that suggests the sexual sin of Zimri and Cozbi, the young lovers who dared transgress “in the sight of all Israel.” The Hebrew word translated “belly,” qevah, means the lower abdomen and can refer to the womb or pubic region, emphasizing that Phinehas caught the young couple in the act. The word translated “chamber” in the ESV (other translations use “tent” or “pavilion”), qubbah, appears only here in the Old Testament. The passage is a little obscure, but the sense is that the couple were engaged in some rite to the Baal of Peor, possibly a fertility ritual. So, what do we know about this pagan deity?

The name Baal-Peor is actually a title, the “lord of Peor.” The location of Peor isn’t known exactly, but it must be near Mount Nebo, where Moses got his only look at the Holy Land. On a clear day, visitors to Nebo today can see the Dead Sea, Jericho, and the Mount of Olives, which is only about twenty-five miles away. Shittim, or Abel-Shittim, was the name given to the place of the Israelites’ camp in the plains of Moab, directly below the western slope of Mount Nebo. Shittim means “acacia,” the desert tree that provided the wood of the Ark of the Covenant. It’s a hardy plant, surviving where most other vegetation can’t because of its resistance to drought and tolerance for salt water.

A team led by Dr. Steven Collins of Trinity Southwest University has been digging since 2005 at a site in Jordan that overlooks the ancient plains of Moab. Dr. Collins is convinced that this site, called Tall el-Hammam, is the biblical Sodom. Based on its estimated population, it would have been the largest city in the Levant in the time of Abraham next to Hazor, near the Sea of Galilee.

The evidence suggests that it was destroyed around 1700 BC by an air blast similar to the 1908 Tunguska event in Siberia. Soil samples taken from the lower city revealed a high concentration of salts and sulphates in the ash layer from the city’s destruction, and the chemical composition of the salts and sulphates was “virtually identical to the chemical composition of Dead Sea water.” So, whatever exploded over the north end of the Dead Sea around the time of Abraham had enough force to drop brine over the lower part of the city. This was devastating—the lower city was built on a hill seventy-five feet above the Jordan valley!

Further investigation of the plain itself, the Kikkar, revealed that the salty water essentially poisoned the ground. It was at least six hundred years—about the time of Saul, David, and Solomon—before agriculture and civilization could resume. So, when the Israelites arrived on the plains of Moab, it was well named Abel-Shittim, the “meadow of acacias”—because virtually nothing would grow there besides salt-tolerant acacia for another 250 years.

Now, why is all of that relevant? Because the area east of the Dead Sea, and especially near the ruined city of ancient Sodom, was a place where it was believed that the dead intervened in the affairs of the living. In fact, two of the stops along the Exodus route refer to places where the veil between worlds was believed to be thin.

And the people of Israel set out and camped in Oboth. And they set out from Oboth and camped at Iye-abarim, in the wilderness that is opposite Moab, toward the sunrise. (Numbers 21:10–11)

The name of the first, Oboth, derives from ʾôb, which refers to necromancy, the practice of summoning and consulting with spirits of the dead. This is the Hebrew behind the English word “medium,” as in the woman consulted by Saul to summon the spirit of Samuel.

This is a controversial topic among Christians. Those of us who take the Bible seriously are inclined to believe that there’s no such thing as ghosts. But there is nothing in the biblical account to suggest that the spirit who delivered God’s message to Saul was anything but the ghost of Samuel—who, it’s important to note, was called an elohim as he emerged from the earth.

“Elohim” is not a proper name, and it doesn’t refer specifically to “gods.” It’s a designator of place, like “American” or “New Yorker.” Spirits live in the spirit realm, but not all spirits are equal. Some are archangels and others are demons, but all are spirits. In the same way, spirits are all elohim, even the spirits of dead humans, but there is only one capital-E Elohim.

Interestingly, this casts new light on the name of one of the giants who fell before the swords of David’s mighty men.

There was war again between the Philistines and Israel, and David went down together with his servants, and they fought against the Philistines. And David grew weary. And Ishbi-benob, one of the descendants of the giants, whose spear weighed three hundred shekels of bronze, and who was armed with a new sword, thought to kill David. But Abishai the son of Zeruiah came to his aid and attacked the Philistine and killed him. (2 Samuel 21:15–17)

Contrary to the most common definitions of the name, the giant wasn’t Ishbi-benob, he was Ishbi ben Ob—“Ishbi, son of the medium”! And the “descendants of the giants” (yĕlîdê hā-rāphâ) were probably a Philistine warrior cult that venerated the “mighty men who were of old,” a practice that had persisted for at least 1,500 years by the time of David.

Derek Gilbert Bio

Derek P. Gilbert hosts SkyWatchTV, a Christian television program that airs on several national networks, the long-running interview podcast A View from the Bunker, and co-hosts SciFriday, a weekly television program that analyzes science news with his wife, author Sharon K. Gilbert.

Before joining SkyWatchTV in 2015, his secular broadcasting career spanned more than 25 years with stops at radio stations in Philadelphia, Saint Louis, Little Rock, and suburban Chicago.

Derek is a Christian, a husband and a father. He’s been a regular speaker at Bible prophecy conferences in recent years. Derek’s most recent book is The Great Inception: Satan’s PSYOPs from Eden to Armageddon. He has also published the novels The God Conspiracy and Iron Dragons, and he’s a contributing author to the nonfiction anthologies God’s Ghostbusters, Blood on the Altar, I Predict: What 12 Global Experts Believe You Will See by 2025, and When Once We Were a Nation.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!